Direct Taxation in the Early History of Sierra Leone

Direct Taxation in the Early History of Sierra Leone

HISTORICAL period dating is a difficult business and can never be too precise. Before the declaration of the Protectorate over the hinterland in 1896, the government of the Settlement and Colony passed through three distinct phases. 1787—1790/91 the period of virtual self-government or of the proprietorship of Granville Sharp; the period of Charter Company government from 1790/1 to l807 and, following that, the period of Crown Colony Government proper. The early period which forms the matrix of the substance of this paper refers chiefly to the first two periods particularly to the period of Charter Company government. This of course implies that the Sierra Leone referred to in this paper is not the geographical and political expression of today but the legal expression of the Charter of 1791 embracing the area some 20 miles square acquired in 1787 on behalf of the first settlers.

Small as this area was in physical size, the experiences with direct taxation in it were fundamental to the development not only of the smaller settlement but also to that of the larger geographical area which we now know. A study of those experiments is most illuminating not only as a piece of history but also as an object lesson of the role that such little administrative devices can play (in the context of an underdeveloped country) on the course of economic development and on such other minor influences on the course of development as race relations.

In this early phase of Sierra Leone several expedients at direct taxation were attempted. They were all in the nature of property taxes using the term in its widest sense. These included taxes on house and land, on horses and carriages and other domestic animals and a roads tax. Only one of these, the house tax, survives today. It survives in the municipal rates in the municipality of the colony, the house tax in the colony areas outside the municipality and in the Protectorate.

At the time of the commencement of Crown Colony government the colony was almost entirely financed by means of Parliamentary grants-in-aid. Indeed, it is truer to say that local revenue was sought for in aid of Parliamentary grants. From 1800 ad hoc Parliamentary grants were made to the Company government, and from 1804 regular grants were so made in aid of the civil administration of the Settlement and for defence.

The Company government had hoped to finance itself by means of trading profits and by supplementary internal sources of revenue. The onset of the Napoleonic war endangered their highly profitable commercial venture almost from the start and thus intensified their search for internal revenue. The earlier Charters did permit of the collection of revenue for "the interior welfare" of the settlement, and it was primarily with that object in view that the early attempts at direct taxation were made. This was the central focal point of all the earlier forms of direct taxation and that explains the fact that all these taxes or what may, at least, pass for their prototypes were early to be found in a single measure, namely, the Highways Act which was designed primarily for the "making and keeping in repair the highways of the Colony".

The origins of the principles of the Highways "Act" seem to lie in the Regulations in force at the commencement of the Settlement under Granville Sharp. Sharp himself claimed to have based the Regulations on the ancient system of” medieval Frank pledge’’ which, for him, had something almost like divine or, at least, Mosaic sanction. It is not unlikely that the influence of the English Poor Law of the time was also at work. There is moreover, a strong presumption here of the influence also of Adam Smith’s labour theory of value, although no direct connection can be traced. It is well to remember that the “Province of Freedom on the Mountains of Sierra Leone" was very near to Smith’s "rude state of society".

Sharp had fixed a 310-working day year (with eight hours work to the day) for the employable male population out of which the labour of two-tenths or sixty-two days was to be taxed away for the maintenance of the government and for the upkeep of the poor and sick. Hence the state was to be financed by means of a direct tax on the property of labour of the employable male population between the ages of eighteen and sixty and, in addition, the principle of graduation was introduced by the imposition of additional taxation on "pride and indolence ".

That principle minus the graduation element was adopted by the Company government whose Governor and Council on 10th November, 1795, ordered

“That all male Settlers within the said Territory of Sierra Leone, from the age of sixty shall be liable to be called upon for six days work in the course of a year for the clearing and keeping in order the streets and roads within the said territory, and in case any person so liable to be called upon, shall neglect or refuse to obey summons of the Overseers of Roads (to be hereafter appointed) every person so offending shall be fined in the sum of one Dollar: and all female Settlers being in possession of a Town or Farm lot in the said District shall be liable to be called upon to send a man to work six days in the course of a year and shall be liable to the same fine of one Dollar in case of neglecting or refusing to obey the summons of the Overseer as before mentioned.”

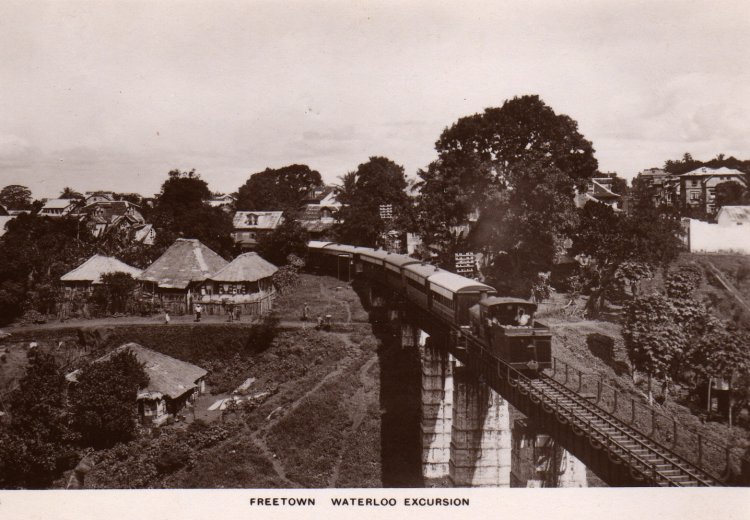

This measure, re-enacted in 1801, was still in force when the Colony was taken over by the Crown in 1807. Together with its amendment of 1812 it became the foundation-stone of the Road tax in the nineteenth century. This tax had an interesting evolution in the Crown Colony period which the limits of this paper will not permit us to dwell upon. Suffices it to say at this point that, in effect--its anomalies notwithstanding-- it was a very significant factor in the promotion of economic development during the nineteenth century, in particular the development of road communications for the greater part of the period-- a factor which is quite often neglected or minimized.

Of equally basic significance but with exactly opposite effects was the other outstanding device of direct taxation in this early period, namely, the quit rent. This is a subject which has never been given any adequate or objective treatment before.

The quit rent was one of those relics of medievalism which, in the peculiar circumstances of the foundation of the settlement found its unhappy way to it and from the first was attended with difficulties. In West Africa it is peculiar to Sierra Leone. And it is an expedient brimful with lessons on fiscal policy and fiscal administration for underdeveloped countries in general. Financially, the quit rent was not a very profitable tax1; but the experiment left a deep influence on the course of economic development in the country.

1In 1796 it was estimated to yield about £200 (currency) p.a.. but Governor Ludlam (1801) reckoned it would yield no more than £100 p.a.--the cost of collection from 1799, when a collector of quit rent was appointed, varying between £15 and £20 p.a.

The first (Nova Scotian) Settlers were each promised a grant of twenty acres of land together with an additional ten acres for his wife and five acres for each child.1 And although the Company had originally decided that the Settlers, irrespective of race, should have the land upon such terms and subject to such charges and obligations as they themselves (i.e. the company) should later determine with a view to their general prosperity2; its agent to the Settlers in

First Nova Scotian Allotment.3

| Acreage | No. of Allotments | Total Acreage |

| 1 | -- | -- |

| 2 | 101 | 202 |

| 3 | 15 | 45 |

| 4 | 120 | 480 |

| 5 | 12 | 60 |

| 6 | 116 | 696 |

| 7 | 44 | 308 |

| 8 | 32 | 256 |

| 9 | 35 | 315 |

| 10 | 15 | 150 |

| 11 | 8 | 88 |

| Total | 498 | 2600 |

Nova Scotia had assured the latter that quit rent was unjust and ought not to be imposed.4 Moreover, in the printed promise of land given to each of the intending Settlers and signed by Messrs. Clarkson and Hartshorne their lands were promised them “free of expense”. This may have been intended to refer to the expense of purchase only. In medieval England such a practice was frequent while not absolving the tenant from the payment of quit rent. This was also true for the settlement of New South Wales (Australia). The Settlers had, however, been told and had expressed willingness to gradually pay back the expenses incurred by the company in establishing the settlement and to pay taxes and contribute to the expenses of supporting the Governor and the poor.5 When the first allotments were due to be determined, the peculiar difficulties of the early settlement suggested the inexpediency of giving each individual his full share of twenty acres at once “as so large an

1 C.B.Wadstrom: Essay on Colonization (1794), part ii, p. 29.

2 Letter from Z. Macauley to the Colonists of Sierra Leone inset to C.O. 270/4, ff. 161-2.

3 Original Source: Montague's Ordinances, vol. iv (London, H.M.S.O. 1870). There were also 13 Reserves totalling 25 acres among the allotments.

4 C.O. 270/6, fol. 292.

5 Letter from Z. Macauley, loc. cit.

allotment would necessarily throw many of the settlers to an inconvenient distance from the town and river” where they would be unprotected.1 With the acquiescence of the Nova Scotians it was then decided to allot them four acres each in the first instance, the right being reserved to them of claiming the remainder as it should be wanted. The allotments actually made are summarized in Table I.

Meantime, the Company had decided “ that no quit rent should be charged till midsummer 1792; that then, an annual quit rent of not more than 1s. an acre should be payable for two years, in half- yearly payments; that from that time, i.e. Midsummer, 1794, the rent should be raised to not more than 2 per cent tax on the gross produce of the lands; and that at the end of three years more, that is, Midsummer, 1797, the rent should be again raised, and fixed at the rate of not more than 4 per cent on the gross produce of the lands”3 It was also decided that if one-third part of the lots was not cleared and cultivated in two years and two-thirds in three years then the whole should be forfeited to the Company.

The allotments were completed between November, 1792, and March, 1793, in time for the crop of the latter year. There was some dissatisfaction with the allotments.4 Hence on 1st September, 1793,

1 Prince Hoare: Memoirs of Granville Sharp (London. 1820), part iii. pp. 280-1.

2In the case of the Maroon allotments at Kingtoms Point—the Maroons having assisted in putting down the Nova Scotian rebellion in 1800—were worse still. Of 111 grants recorded only one was of 4 acres. The rest of them varying from 1/3 acre to 3 2/3 acres, the majority being below 2 acres. And four considerably larger grants covering the entire foreshore were made to whites including Justice Bannister and the Heddles. Vide Montague's Ordinances, loc. cit.

3C.O. 270/4, ff. 144 et seq.

4 There was some dissatisfaction over the lots falling to Whites and those reserved to the Company. This was probably not unconnected with the inter-racial distrust born of the fact that “ all the white people...sent out in 1788 to assist in supporting the settlement had been wicked enough” as Sharp bewailed "to go into the service of the Slave Trade at the neighbouring factories" and helped to enslave their follow black settlers. Vide Letter of Granville Sharp to the Rev. Samuel Hopkins dated 26th July 1789, quoted Hoare, op. cit., p. 343. It is also connected with the conflict of jurisdiction or “revolutionary” shift of jurisdiction. During the proprietorship of Sharp there was virtual self-govemrnent and the people had made their own grants and agrarian law. Vide Note 1, p. 31.

the Governor and Council decided to offer, on quite liberal terms. some twenty families of the dissatisfied settlement on a portion of the Bullom Shore which had just been acquired from the indigenous Chiefs. The terms were:

(1) the families were not to be divided

(2) each individual to be given a piece of land equal in quantity to that already allotted at Sierra Leone together with a town lot of seventy-four acre extent provided

(3) they shall relinquish the town and farm lots already allotted them in Sierra Leone as well as every claim of land or for compensation instead which they may have had on the Company

(4) they shall agree to pay quit rent of one bushel of clean new rice for each of their town lots and one bushel of rice for each acre of land on the farm lots

(5) to obey the laws of the settlement

(6) to be called out for purposes of defence

(7) not to transfer the land without the consent of the Governor and Council

(8) to agree to clear the town lots and build dwellings on them in the way prescribed by the Government Agent and that to be done by 1st May. 1794

(9) that in three years from 1st January, 1794, at least one-fourth of the land granted shall be cultivated otherwise all allotment exceeding one-fourth which remains uncultivated to be forfeited by the Company.

The liberal terms of this offer were so patently confirmatory of the suspicion the settlers had that the Company wanted to dispossess them of Sierra Leone in favour of white settlers that the scant regard which the Hundredors and Tythingmen gave to it is understandable. The suggestion of payment in kind especially in rice is bound to be regarded with suspicion. At that time, the price of rice appeared to have been fluctuating. Old stocks of rice at the Company’s stores were being sold at £10 per ton whereas rice from the Great Scarcies was estimated at £12 per ton.2

1C.O. 270/2, ff. 109-12-- If payment in rice proved inconvenient to either party it may be commuted into “as much money as the above quantity of rice would bring at market"

2CO. 270/2, fol. 94-- allowing for a profit of 10 per cent.

There was some friction in collecting the quit rent. The whole atmosphere was complicated by the difficulties of 1794 when French privateers sacked, ravaged, and pillaged the settlement.

Between 1794 and 1801 the quit rent proved to be one of the most difficult problems with which the government had to contend. The whole climate, by that time, was befogged. There was an inflationary situation which was, in part at any rate, a result of the Napoleonic wars and the high food prices following from the shortage of supplies. There were the after-effects of the French attack itself aggravated by what one commissioner described as “considerable indiscretion on the part of the government’’ to enforce restitution of the Company’s property which had been diverted or deemed to have been diverted during those outrages. The administration too did not appear to have had a high standing for virtue and honesty. According to Thomas Ludlam (a later Governor) there were “those tyrannies imposed by the deficiencies of the Company’s servants e.g. the storekeeper charging the people for supplies they did not have”.2 Finally, there was the Governor’s insistence on the Company’s earning monopoly profits.3 Consequently, by that time, the quit rent issue became fused with a much wider issue, namely, what amounted to a denial of the sovereignty of the Company government and the asserting of the settlers’ right of self-government which, to all intents and purposes, they had enjoyed under Granville Sharp.

In 1796 it was agreed to tighten up the administration and collection of the quit rent. For that purpose certificates were to be granted to the proprietors of town lots signed by the Secretary on behalf of the Government and grants were to be prepared to be delivered to the proprietors of country lots by August, 1797. At the same time the quit rent was fixed at 1s. per acre per annum payable half-yearly as from 1st January, 17974. Seven months later, on the

2 C.O. 270/6, fol. 292.

3C.O. 270/3, fol. 49.

4 C.O. 270/4, fol. 97. .

By the time the grant certificates were issued, the quit rent issue had become the rallying ground of discontent and general opposition to the government. The peace and tranquillity of the settlement was disturbed and the opinions of the” Hundredors & Tythingmen” on the subject of the quit rent were made the test by which they were thought worthy of the confidence of the people. It became their local election banner and all who had ventured to support it were thrown out of office and men more congenial to the social temper elected in their places. By the second half of 1797 the country was in a state little short of anarchy although actual violence was avoided. A compromise was reached and the quit rent was not then enforced. After about a year of normalcy the truce was broken by the arrival of Mr. Gray with instructions from the Court of Governors to enforce the quit rent. Hasty measures of price-control and regulations against extortion were undertake and an attempt was made to use the technique of remission of school fees as an incentive to payment of the quit rent and so enforce it by the back door.3 This proved a complete failure and the people were alleged to have acted rather as if by sending their children to school they were conferring a benefit on the government.

The opposition became formidable and since the peace of the settlement seemed to lie in danger the collection of the quit rent was suspended and the condition on which the children were admitted to school was relinquished a few months later.4 These measures were not in themselves sufficient to check the drift towards revolution especially as the issue of the quit rent had come to be

2 C.0. 270/4, fol. 23.

3 C.O. 270/4, ff. 235—6.

4 C.0. 270/4, ff. 311—14.

espoused to that of the settlers’ claim to a right to regulate immigration. A conflict, therefore, ensued but the Company government was saved by the timely arrival of the Maroon Settlers, to whom they had promised land, and some regular soldiers by whose aid the settIers were overcome.

When in 1801 the newly appointed Governor reviewed the issue of the quit rent, he found it (with astonishing objectivity for his time) wholly defective; but his remedy was a mere patch work. The remedy was two-fold:

(1) to reduce the quit rent to all widows and orphans on lands already granted to ten cents and one cent per acre respectively

(2) for all others to establish rates as follows:

(i) to everyone cultivating one-quarter of his land, ten cents per acre

(ii) to everyone cultivating one-half of his land, one cent per acre.

.

The object, clearly, was to relieve the widows and orphans and by relieving them restore confidence to the people in the security of their tenure; and, by a differential scale of rent on cultivated and uncultivated land to give an incentive to cultivation. The rationale is simple but it is doubtful whether those objects were in any measure achieved before the final abotition of the quit rent under the Company government in 1803.

Before going into that as well as the economic consequences of quit rent generally, it may be of advantage to consider briefly but in rather more detail the general theory or principles of quit rent.

The quit rent was a yearly payment—- a relic of the feudal system— made by the copyholders and freeholders of an English manor to its lord. It was called quit rent because it acquits the tenant of all dues and obligations to the land. They were of two kinds. According to Blackstone ,“ rents of assize are the certain established rents of the freeholders and ancient copyholders of a manor, which cannot be departed from or varied. Those of the freeholders are frequently called chief rents, reditus capitales; and both sorts are indifferently denominated quit rents, quieti reditus ; because thereby the tenant goes quit and free of all other services.” 1 Blackstone further tells us that it originates from a theory (which is indeed a fiction originating

1 Blackstone, Sir Wm., Commentaries, Book II, pp. 42 and 51.

(1) it is a return made by freeholders (and copyholders) for services for which land might be granted

(2) it cannot be varied---increased or diminished--or departed from and so it must be certain or capable of being reduced to certainty by either party

(3) it issued out of the land so held

(4) it could be distrained by the lord in whosoever's hands the land was

(5) it must not be a part of the hereditaments so held and, therefore, there must exist a corporeal hereditament, e.g. land but not intangible items of property so that the owner can distrain for non-payment

(6) it must be a profit.

It was treated as a thing--a tenement--just like the land.1 In the middle ages it was regarded as a thing, issuing from the land and recoverable by real actions.2 And before 1833 it was invariably regarded as an incorporeal thing.3

When the Crown’s powers devolved on or came to he vested in the modern State, the fiction on which payment of the quit rent was based became no longer tenable. Continuation of payment meant payment to a body other than the sovereign lord and, in fact, the payment went to benefit individual landlords. We, therefore, find the quit rent being progressively abolished. In England where the theory persisted longer, the Law of Property Act, 1922, envisaged its extinction and they have at last been extinguished as from 1st November, 1950.4

1 Holdsworth, Sir Wm., An Historical Introduction to the Land Law (1927), p. 97.

2 Holdsworth, loc. cit., p. 98--Sir William also tells us that "real action" meant (by the close of the Middle Ages) an action in which the specific thing demanded could be recovered. Op. cit., p. 11.

3The Act 3 and 4 William iv c. 27 Sec. 36(1833) abolished real actions. Legally this tended to give reins to the idea that rent is not so much an incorporeal thing as a payment done by virtue of a contract.

4Cf. Postponement of Enactments (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, 1939 (Manorial Incidents Extinguishment), Order, 1949, issued as Statutory Instruments, 1949, No. 836, dated 29th April, 1949.

From the first also it violated the principle of invariability.

The quit rent, as a medieval incident, was in the nature of a negatively progressive income tax which became less burdensome as productivity improved. The quit rent, in the early history of Sierra Leone, on the other hand, was in the nature of an uncertain property tax which grows more and more burdensome on the settler the more efforts are made to improve the land. Ludlam s reform (outside its application to widows and orphans) was rather in the nature of a regressive tax on gross income--part property and part income tax.

Also, the manner of its administration was unfortunate. As to the land question itself. The imposition of the rent induced the settlers to pose a claim to their abstract right to the land itself. Here the point must not be overlooked that the transition from the proprietorship of Sharp to Charter Company government must itself have appeared a revolution to the people the full significance of which would be incomprehensible to minds too little developed to enter into the subtleties and intricacies of English land law. Under the proprietorship of Sharp the land belonged to the settlers who granted portions of it "by the free vote of their own common

126 C. M. H. Clark and L. J. Pryor : Select Documents in Australian History (1788-1850) (London, 1950), p. 220.

Very little is known about the effects of the quit rent experiment. We can only speculate about them. There were, no doubt, immediate and short-term effects and there have certainly been long-term effects. As indicated before the financial harvest was not likely to have been a rich one. Of the immediate effects, the most spectacular were the mass movement away from the land, the neglect of cultivation, emigration and consequent depression in agricultural production. Ludlam (1801) tells us that “ most of the farmers who determined not to pay the quit rent took active part in the insurrection and left the country”. Consequently, one of its primary effects was to stimulate the emigration of the farmers--a loss to the settlement of those with the only experience in cultivation and having the agricultural technique, rudimentary and inefficient, perhaps, but reasonably effective. The remainder of the farmers who oppose the quit rent he similarly reports as having “quitted their lands and suffered their farms to fall to ruins".2 This must have had a serious effect on production in the settlement especially as “not 10% of the population had not at one time or the other opposed the quit rent “. The loss of output, in turn, must have aggravated scarcity of provisions and the inflation which was already rampant in the settlement. The psychological effects of this state of affairs, no doubt, was conducive to that “good conduct of all description of persons” during the Timanee wars which ensued and

1 Letter of Sharp dated 5th October, 1891 to a “Dr. friend” reproduced in Memoirs, op. cit., p. 360.

2 Thus whereas Ludlam estimates that there were between 600 and 700 acres under cultivation before the insurrection (vide Madden Report, 1841, p. 261), Commissioner (later Governor) Dawes estimated that there were only 448 acres under cultivation in 1810 "about one-half of which had been cleared within these last thirteen months" reflecting the extent to which cultivation had declined in the meantime, i.e. to about 224 acres.—C.O. 267/29.

which, among other things, induced Governor Day’s administration to abolish the quit rent in 1803.1

Apropos the non-farming classes, Ludlam also tells us that the greatest part of them chose to surrender their farms rather than pay the quit rent or oppose it. There was no incentive for them to retain the land. Either, in the heat of the controversy, they might have considered that by keeping possession their lives were endangered or, which is more likely, because of the inflation and the consequent rising cost of farm labour or the infertility of the upland farms, it was not profitable to retain possession while the impost was in force.

No strife can grow up there from faction.” (Milton.)

There was consequently a mass exodus from the land and loss of the best of the agricultural skills the settlement previously possessed. The widows and orphans, it is believed, suffered more. Again, Ludlam writes:--

"...the fears of the people that the quit rent may deprive their children of their lands, are not wholly without foundation. The administration of the late H. Lawrence’s affairs is in my hands; and his eldest son and heir to his land, lives with me. I am fully of opinion that it will be more eligible to surrender the land, if I cannot find a purchaser for it, than to keep it by paying a shilling an acre till the child is of age. I think there is sufficient probability that the money it would by that time amount to will then purchase him an equal quantity of land shall he be disposed to become a farmer, and if he follows any other profession will certainly be of more use in his own hands. In many similar cases it may neither be easy to find a person to advance the money yearly during the non-age of the child, nor for the child to pay it at once on his coming of age. It is right also to observe that the quit rent may be sensibly felt by those who cultivate to any extent whether Europeans or others. They can scarcely avoid having a considerable quantity of land out of cultivation in many cases much more than they can be expected to keep in a cultivated state, and the quit rent on the whole of their lands will not be inconceivable.” 2

From this he concluded that this tax might have operated to dispossess this class of persons (widows and orphans) of their lands. It is not unlikely too that with the inflation and consequent

2 C.0. 270/6, fol. 297.

The long-run effects must be in the nature of a shock. The security of ownership and possession which had been nursed and taken for granted during the period of Frank-pledge government was completely shattered and, during the Company period and after, the whole atmosphere was overcast with clouds of uncertainty, leaving a sense of insecurity with regard to tenure and doubt as to ownership of the land itself. “The people looked upon the quit rent as in fact taking away the value and security of their lands” (italics mine).

The most significant long-term effect is the legacy of suspicion, insecurity, and uncertainty handed down, as it were, through the inheritance of tradition from generation to generation. It must have had a profound influence on development, particularly agricultural development, throughout the history of the colony. If, indeed, there is anything like race memory, it is not unlikely that it is the memory of this experience which--revived by the land clauses to the Protectorate Ordinance, 1896--threw the Protectorate Chiefs into the arms (and sympathy) of the Colony people who were known to have been in complete sympathy and support of the latter in their struggle against Governor Cardew. The suspicion that the white man was going to dispossess the Africans of their lands runs throughout the history of the colony. It is largely responsible for race relations in it. There can be no doubt that the quit rent troubles contributed in no small measure to it if it wasn’t even the foundation for those fears. That experience at the very prime of the settlement was fundamental not only to the course of its economic development but also of race relations.

The tax was first abolished in 1803. The Crown Colony, therefore, did not actively inherit it from the Company. But in 1812, the new government revived the expedient after taking steps to systematize and improve its administration. It was finally abolished in 1832.1 Even so, it does not appear to have been much better in operation than its predecessor. From the first, it began to impose similar hardships on the people. In 1813, the first year of its operation, there were no less than fourteen defaulters with rents approaching £5 outstanding whose lands were accordingly all confiscated to the

There was also a town lot listed as belonging to the “Estate of Anty Hill” 2 which indicates that the rent was still operating adversely against inheritance as Governor Ludlam had apprehended. It is, therefore, difficult to resist Lord Goderich’s conclusion that the scheme of deriving a revenue from quit rents “is condemned both by reason and experience ".3

The experiences with these two devices at direct taxation in the early history of this country are sharply contrasted. The one, as we have already seen, brought in considerable benefits to the community whereas the other literally led to untold evils. There are, no doubt, many lessons to be learnt from these experiences--lessons on fiscal policy and lessons on administration in an underdeveloped country. I leave it to the audience to draw out those lessons.4 I may, perhaps, be permitted to observe that these devices in the context

2 CO. 270/14, fol. 50.

3Dispatch of Lord Goderich to Governor Darling dated 9th January, 1831; quoted C. M. H. Clark and L. J. Pryor, op. cit., p. 223.

4In view of the trend of the discussions following the paper, it has appeared wise to direct attention to some of the more salient conclusions. In the first place, besides violating the known Adam Smithian maxims, the tax was completely divorced from any relation to taxable capacity. The first lesson, therefore, is that taxation to be satisfactory must be related, in some way, to the taxable capacity of the community. In the next place, the experience of the quit rent showed (although it was operated in a non-democratic atmosphere) that where practically the whole population was opposed to the device, compulsion could lead to the unbalance of the economic and social stability of the society. But for the almost accidental arrival of the Maroons, a successful political revolution might have been effected. From this it follows, thirdly, that apparently insignificant fiscal devices can have ramifications far beyond the mere collection of revenue. Consequently, governments in adopting fiscal measures must take into consideration, as far as it is possible to do so, these wider implications of a tax policy. Lastly, the administration and abuse of these fiscal devices showed that a commercial company (as the experiences with the East India Company so well confirms) cannot be trusted to carry out its commercial functions simultaneously with the functions of government without sacrificing the latter to the former and so becoming the purveyor of inestimable misery and the disturbance of the social equilibrium of the society.

of the early history of this colony explode the popular fallacy that "a good thing does not last". The quit rent was abolished in 1832 although not before it had laid the basis for a less noxious land tax. The road tax continued to 1872 and, but for the "hasty" action of Governor Pope Hennessey could very well have evolved to an equitable direct tax long before the income tax of 1943.

What's Your Reaction?